Discover How Senior Living 4.0 Can Help You Take Care of Your Loved Ones

Discover How Senior Living 4.0 Can Help You Take Care of Your Loved Ones

Discover How Senior Living 4.0 Can Help You Take Care of Your Loved Ones

Discover How Senior Living 4.0 Can Help You Take Care of Your Loved Ones

Discover How Senior Living 4.0 Can Help You Take Care of Your Loved Ones

Discover How Senior Living 4.0 Can Help You Take Care of Your Loved Ones

THIRD INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

From 1950 onward, Main Street faced a cultural shift as the postwar boom separated families across suburbs and states. Older generations, once central in multigenerational homes, often found themselves distanced from daily family rhythms. Communities responded by rebuilding social anchors — churches, clubs, and cafés where seniors could stay connected and visible. The rise of senior centers, volunteer programs, and local outreach in the 1960s through the 1980s marked a shift from caretaking to inclusion, turning companionship into civic duty.

Connection became a shared responsibility, not a private burden.

As the digital age arrived, Main Street adapted again. By the 1990s and 2000s, assisted-living communities began blending independence with social life, while libraries and schools introduced computer literacy classes for older adults. When

Social Impacts of Senior Living 3.0

Infrastructure Impacts of Senior Living 3.0

Economic Impacts of Senior Living 3.0

Affordable long-distance calling let grandparents schedule visits, share news, and resolve worries in time, shrinking distance between towns and keeping family decisions collaborative across generations.

Economic Impacts of Senior Living 3.0

Infrastructure Impacts of Senior Living 3.0

Economic Impacts of Senior Living 3.0

Local news, church services, and hometown sports aired widely, giving seniors shared topics with neighbors and grandchildren, building routine gatherings and intergenerational conversations at home.

Infrastructure Impacts of Senior Living 3.0

Infrastructure Impacts of Senior Living 3.0

Infrastructure Impacts of Senior Living 3.0

Instant cameras, then digital albums and cloud galleries, let grandparents trade milestones quickly, display memories at gatherings, and spark stories that kept family identity strong.

Educational Impacts of Senior Living 3.0

Infrastructure Impacts of Senior Living 3.0

Infrastructure Impacts of Senior Living 3.0

Transistor and digital advances improved clarity in conversations, clubs, and worship, reducing isolation, restoring confidence, and inviting seniors back into bustling Main Street community life.

OUR THREAD OF TIME - INNOVATIONS TO IMPROVE THE HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Long Distance Calling

Community Television Gathers Living Rooms

Community Television Gathers Living Rooms

Affordable long-distance calling let grandparents schedule visits, share news, and resolve worries in time, shrinking distance between towns and keeping family decisions collaborative across generations.

Community Television Gathers Living Rooms

Community Television Gathers Living Rooms

Community Television Gathers Living Rooms

Local news, church services, and hometown sports aired widely, giving seniors shared topics with neighbors and grandchildren, building routine gatherings and intergenerational conversations at home.

Hearing Aids Amplify Social Participation

Community Television Gathers Living Rooms

Hearing Aids Amplify Social Participation

Transistor and digital advances improved clarity in conversations, clubs, and worship, reducing isolation, restoring confidence, and inviting seniors back into bustling Main Street community life.

Polaroids to Photo Sharing Platforms

Community Television Gathers Living Rooms

Hearing Aids Amplify Social Participation

Instant cameras, then digital albums and cloud galleries, let grandparents trade milestones quickly, display memories at gatherings, and spark stories that kept family identity strong.

Video Calling Reunites Dispersed Families

Video Calling Reunites Dispersed Families

Video Calling Reunites Dispersed Families

From Skype to FaceTime, grandparents attended birthdays and recitals virtually, read stories, and coached recipes, restoring eye contact and warmth across states and military deployments.

Medical Alerts and Independent Living

Video Calling Reunites Dispersed Families

Video Calling Reunites Dispersed Families

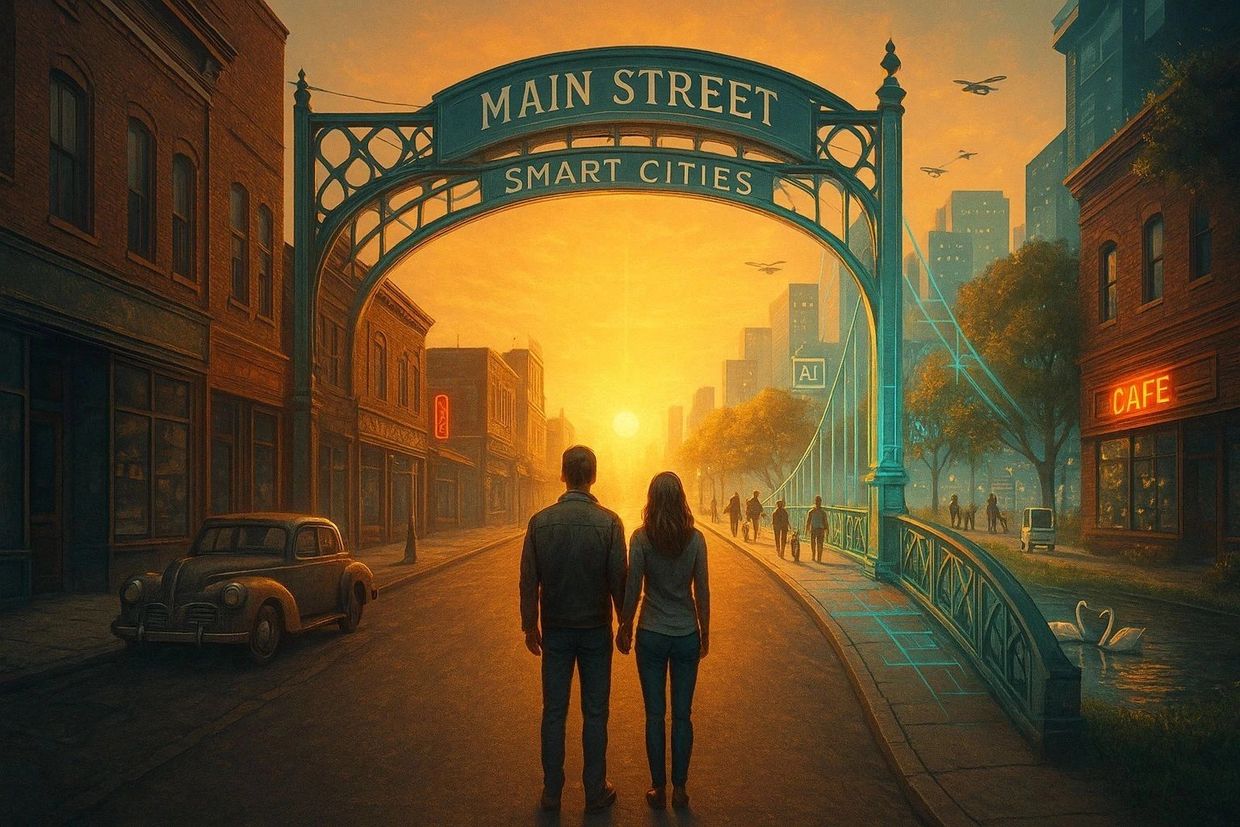

We’re taking our mission nationwide—bringing Main Street Smart Cities to regions across America, where heritage and innovation unite to restore connection, purpose, and community pride.

Smart Homes Simplify Daily Coordination

Video Calling Reunites Dispersed Families

Smart Homes Simplify Daily Coordination

Voice assistants, reminders, and shared calendars helped track medications, groceries, and chores; relatives coordinated tasks remotely, reducing friction and freeing time for actual visits together.

Senior Living 3.0 Online Course

Video Calling Reunites Dispersed Families

Smart Homes Simplify Daily Coordination

We’re taking our mission nationwide—bringing Main Street Smart Cities to regions across America, where heritage and innovation unite to restore connection, purpose, and community pride.

SENIOR LIVING 3.0 VIRTUAL REALITY HISTORY WORLDS

Direct-Dial Telephone Network Expansion

Digital Hearing Aids, Implants, Captioning

Direct-Dial Telephone Network Expansion

Direct-dial long distance shrank miles between households, enabling frequent calls, holiday check-ins, and quick coordination—strengthening senior-family ties without operators, postcards, or frustratingly delayed letters.

Affordable Jet Travel And Highways

Digital Hearing Aids, Implants, Captioning

Direct-Dial Telephone Network Expansion

Cheaper flights and improved highways made multigenerational visits realistic, sustaining face-to-face rituals—birthdays, graduations, regular caregiving weekends—that kept families bonded across states and seasons.

Home Camcorders, VCRs, And DVDs

Digital Hearing Aids, Implants, Captioning

Digital Hearing Aids, Implants, Captioning

Recording birthdays, ballgames, and reunions let memories circulate. Seniors replayed moments, mailed tapes or discs, and participated in storytelling that bridged distance, decades, and generations.

Digital Hearing Aids, Implants, Captioning

Digital Hearing Aids, Implants, Captioning

Digital Hearing Aids, Implants, Captioning

Smarter amplification, cochlear implants, and TV captioning restored conversations and participation, reducing isolation at gatherings, worship, service, and town halls.

MEET BREEZY AI - YOUR MAIN STREET CITIES RETAIL HISTORY GUIDE

MEET BREEZY AI

Main Street’s transformation through the Third Industrial Revolution brought sweeping improvements that redefined how seniors lived, traveled, and stayed connected. The early decades introduced dependable power grids, paved streets, and expanded hospital systems, giving older adults unprecedented access to safety and care. The introduction of air conditioning, refrigeration, and modern plumbing stabilized home life, while new suburban infrastructure and transit routes connected neighborhoods to clinics, shops, and community centers. These were years when the groundwork for senior independence was laid—when design began to meet human need.

By the 1970s and 1980s, accessibility moved from an afterthought to a civic responsibility. The Americans with Disabilities Act reshaped sidewalks, ramps, and public transit, allowing seniors to

Senior Living 4.0 Hotel Tech Stations

Senior Living 4.0 Gas Station Tech Stations

Senior Living 4.0 Retail Tech Stations

Opened regional access to hospitals, VA clinics, and adult children. Paratransit and volunteer ride programs scale because travel times dropped and routes standardized.

Senior Living 4.0 Retail Tech Stations

Senior Living 4.0 Gas Station Tech Stations

Senior Living 4.0 Retail Tech Stations

A single number plus location services cut response times for falls, strokes, and house fires—life-saving for older adults living alone.

Senior Living 4.0 Restaurant Stations

Senior Living 4.0 Gas Station Tech Stations

Senior Living 4.0 Gas Station Tech Stations

From information access to video calls with family and doctors. Broadband turned libraries and senior centers into digital lifelines.

Senior Living 4.0 Gas Station Tech Stations

Senior Living 4.0 Gas Station Tech Stations

Senior Living 4.0 Gas Station Tech Stations

Reliability + coverage made phones, GPS trackers, and medical-alert wearables actually useful outside the house.

REGIONAL SENIOR LIVING 4.0 HISTORY CAMPAIGNS

San Diego Senior Living History

Orange County Senior Living History

Orange County Senior Living History

Public television (e.g., instructional series, health shows) brought expert guidance into living rooms. Seniors learned through clear, paced explanations without leaving home.

Orange County Senior Living History

Orange County Senior Living History

Orange County Senior Living History

Lifelong-learning courses, basic computing, and language classes became affordable and local. Campuses + senior centers built the “come as you are” pathway into new skills.

Los Angeles Senior Living History

Orange County Senior Living History

Los Angeles Senior Living History

VHS/DVD and community cable let seniors pause, rewatch, and learn at their own tempo—exercise, history, how-to, and caregiver education moved from one-time events to on-demand.

Main Street Innovators Podcast

Orange County Senior Living History

Los Angeles Senior Living History

Intro classes at libraries and senior centers demystified typing, file basics, and simple programs. This set the foundation for email, telehealth portals, and online services later.

Main Street Smart Cities realigns a city's history with its future. Our mission is to ensure that Main Street continues to lead humanity into the Fourth Industrial Revolution. We believe a new dawn is rising again in America. Our nonpartisan campaigns introduce new technologies to rethink what's possible to move humanity forward. - Todd Brinkman, Founder, Main Street Smart Cities

Copyright © 2025 Senior Living 4.0

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.