Discover How Senior Living 4.0 Can Help You Take Care of Your Loved Ones

Discover How Senior Living 4.0 Can Help You Take Care of Your Loved Ones

Discover How Senior Living 4.0 Can Help You Take Care of Your Loved Ones

Discover How Senior Living 4.0 Can Help You Take Care of Your Loved Ones

Discover How Senior Living 4.0 Can Help You Take Care of Your Loved Ones

Discover How Senior Living 4.0 Can Help You Take Care of Your Loved Ones

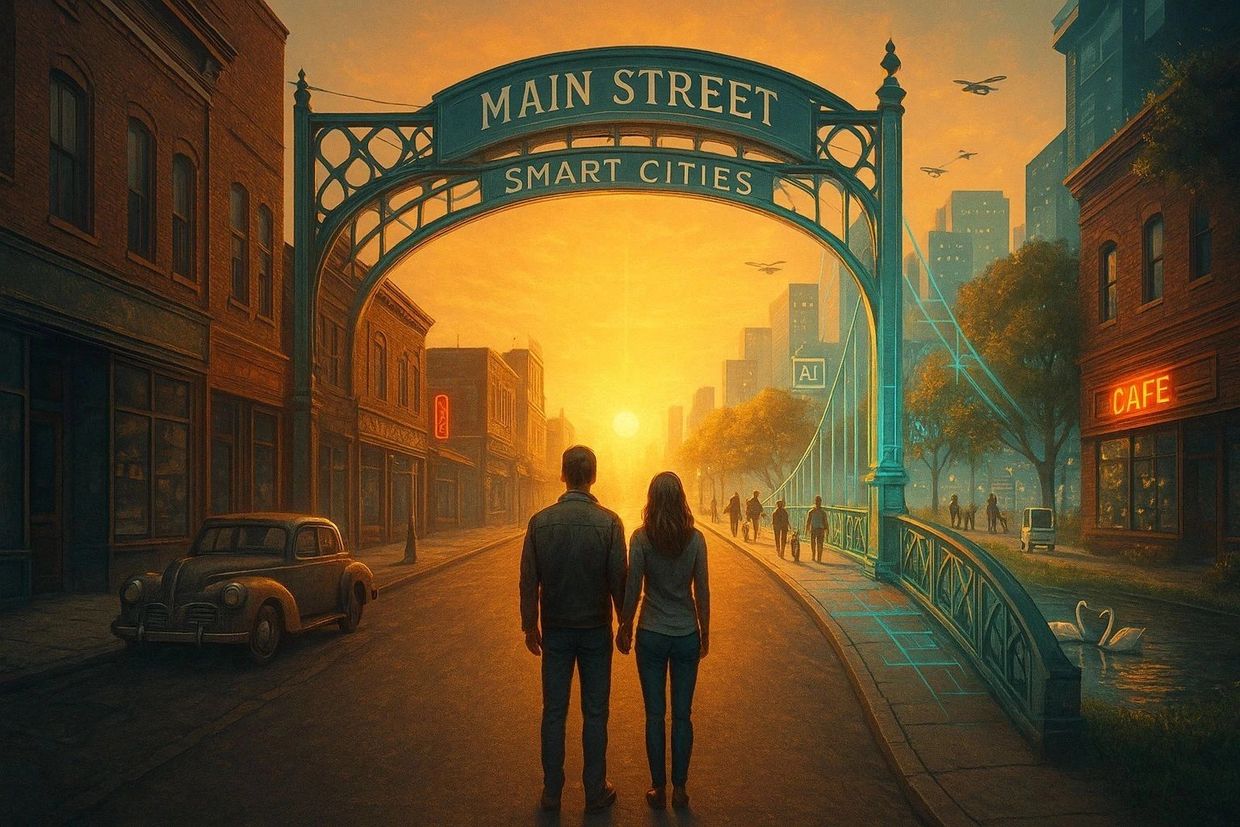

THE RISE OF MAIN STREET CITIES

Main Street America began to recognize the growing needs of its aging population as industrial progress reshaped family life. Mechanization and urban migration drew younger generations into factories and offices, leaving many older adults behind in rural towns or small city neighborhoods. Local churches, women’s auxiliaries, and civic societies became early lifelines—organizing meal circles, letter-writing visits, and neighborhood watch programs that kept elders socially visible rather than isolated.

At the same time, early philanthropic housing projects, such as “homes for the aged,” started to appear near factories and rail corridors, designed not as medical facilities but as modest extensions of community life. Public libraries, fraternal lodges, and park movements offered new shared spaces where generations could meet again on common ground.

Social Impacts of Senior Living 2.0

Infrastructure Impacts Senior Living 2.0

Economic Impacts of Senior Living 2.0

San Diego 4.0 bridges heritage and innovation—uniting technology, empathy, and community design to create Main Street Smart Cities where human connection drives the future of progress.

Economic Impacts of Senior Living 2.0

Infrastructure Impacts Senior Living 2.0

Economic Impacts of Senior Living 2.0

Evenings no longer ended at dusk; seniors enjoyed reading, visiting, and community events illuminated by reliable electric light, fostering safety and togetherness after dark.

Educational Impacts Senior Living 2.0

Infrastructure Impacts Senior Living 2.0

Infrastructure Impacts Senior Living 2.0

Early cars gave families freedom to visit distant relatives, making Sunday drives and small-town reunions more common and strengthening family relationships across rural regions.

Infrastructure Impacts Senior Living 2.0

Infrastructure Impacts Senior Living 2.0

Infrastructure Impacts Senior Living 2.0

Frequent, faster mail delivery meant letters and photographs circulated widely, helping older generations feel remembered and included in family milestones and national progress.

OUR THREAD OF TIME - INNOVATIONS TO IMPROVE THE HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Telephone Bridges Families

Electric Lighting Extends Gatherings

Electric Lighting Extends Gatherings

San Diego 4.0 bridges heritage and innovation—uniting technology, empathy, and community design to create Main Street Smart Cities where human connection drives the future of progress.

Electric Lighting Extends Gatherings

Electric Lighting Extends Gatherings

Electric Lighting Extends Gatherings

Evenings no longer ended at dusk; seniors enjoyed reading, visiting, and community events illuminated by reliable electric light, fostering safety and togetherness after dark.

Automobiles Expand Family Visits

Electric Lighting Extends Gatherings

Postal Service Deepens Connection

Early cars gave families freedom to visit distant relatives, making Sunday drives and small-town reunions more common and strengthening family relationships across rural regions.

Postal Service Deepens Connection

Electric Lighting Extends Gatherings

Postal Service Deepens Connection

Frequent, faster mail delivery meant letters and photographs circulated widely, helping older generations feel remembered and included in family milestones and national progress.

Electric Trolleys Connect Towns

Postal Service Deepens Connection

Electric Trolleys Connect Towns

Public transit let seniors visit family, markets, and churches independently, nurturing civic involvement and neighborhood familiarity within expanding Main Street communities.

Newspapers Unite with Stories

Postal Service Deepens Connection

Electric Trolleys Connect Towns

Local journalism gave seniors daily links to neighbors’ lives, public debates, and community growth, preserving shared purpose amid industrial and social transformation.

Indoor Plumbing Improves Dignity

Postal Service Deepens Connection

Postal Service Deepens Connection

Running water and sanitary systems reduced dependence on others, giving seniors comfort and self-respect, and allowing multigenerational households to live more harmoniously.

Postal Service Deepens Connection

Postal Service Deepens Connection

Postal Service Deepens Connection

Frequent, faster mail delivery meant letters and photographs circulated widely, helping older generations feel remembered and included in family milestones and national progress.

SENOIR LIVING 2.0 VIRTUAL REALITY WORLD

Telephone Links Homes Together

Electric Lighting Extends Social Hours

Electric Lighting Extends Social Hours

The invention of the telephone in 1876 allowed seniors to stay in touch with family and friends, strengthening emotional bonds across growing towns.

Electric Lighting Extends Social Hours

Electric Lighting Extends Social Hours

Electric Lighting Extends Social Hours

Electricity transformed Main Street life, letting older adults participate in evening gatherings, church events, and community discussions safely after dark.

Streetcars Expand Family Visits

Electric Lighting Extends Social Hours

Postal Services Deliver Connection

Electric streetcars, emerging in the 1880s, made intercity travel affordable and convenient, allowing seniors to visit relatives and attend civic events more often.

Postal Services Deliver Connection

Electric Lighting Extends Social Hours

Postal Services Deliver Connection

Expanded mail routes and rural delivery brought personal letters and newspapers directly to senior households, maintaining family contac

MEET BREEZY AI - YOUR SAN DIEGO 4.0 HISTORY GUIDE

CLEAN STREETS, STEADY STEPS

Main Street USA was transformed by a wave of infrastructure advances that quietly redefined how older Americans lived and aged in their communities. Electric power replaced gas lamps and brought reliable light to homes and streets, making evening life safer for seniors and extending their social world beyond daylight. Running water and indoor plumbing reduced the daily strain of carrying buckets and improved public health in aging populations. Paved roads and sidewalks offered cleaner, steadier paths for mobility and community interaction.

The rise of public transit — streetcars and early electric trolleys — connected older citizens to markets, churches, and friends without dependence on horses or family transport. Telegraph and

Senior Living 4.0 Hotel Tech Stations

Senior Living 4.0 Retail Tech Stations

Senior Living 4.0 Retail Tech Stations

Telegraph networks allowed families to share urgent news across states within minutes, bringing distant relatives emotionally closer during America’s expanding industrial era.

Senior Living 4.0 Retail Tech Stations

Senior Living 4.0 Retail Tech Stations

Senior Living 4.0 Retail Tech Stations

Postal reform brought mail directly to rural homes, giving seniors consistent social contact, letters, and newspapers that connected them to family and national life.

Restaurant Tech Stations

Senior Living 4.0 Retail Tech Stations

Restaurant Tech Stations

The telephone gave seniors real-time conversations with relatives for the first time, creating emotional immediacy that handwritten letters could never match.

Gas Station Tech Staions

Senior Living 4.0 Retail Tech Stations

Restaurant Tech Stations

Electric street and home lighting enabled evening gatherings, church events, and reading—helping older adults stay socially active after dark.

REGIONAL SENIOR LIVING 4.0 HISTORY CAMPAIGNS

San Diego Senior Living 2.0 History

Orange County Senior Living 2.0 History

Orange County Senior Living 2.0 History

Fast communication over distance let families stay emotionally close, sharing major life events instantly for the first time across towns and states.

Orange County Senior Living 2.0 History

Orange County Senior Living 2.0 History

Orange County Senior Living 2.0 History

Early home telephones allowed seniors to talk directly with distant family, restoring conversation and presence even when travel was difficult or expensive.

Los Angeles Senior Living 2.0 History

Orange County Senior Living 2.0 History

Los Angeles Senior Living 2.0 History

Electricity brought night classes, reading circles, and safer evening gatherings—helping older adults rejoin community activities once limited by daylight.

Main Street Innovators Podcast

Orange County Senior Living 2.0 History

Los Angeles Senior Living 2.0 History

Expansion of Carnegie libraries provided free access to books and lectures, encouraging lifelong learning and connection within civic spaces.

Main Street Smart Cities realigns a city's history with its future. Our mission is to ensure that Main Street continues to lead humanity into the Fourth Industrial Revolution. We believe a new dawn is rising again in America. Our nonpartisan campaigns introduce new technologies to rethink what's possible to move humanity forward. - Todd Brinkman, Founder, Main Street Smart Cities

Copyright © 2025 Senior Living 4.0

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.